Bitcoins Value: Mining

The decision to mine for bitcoin comes down to profitability. A rational individual would not undertake mining if they incurred a loss in doing so.

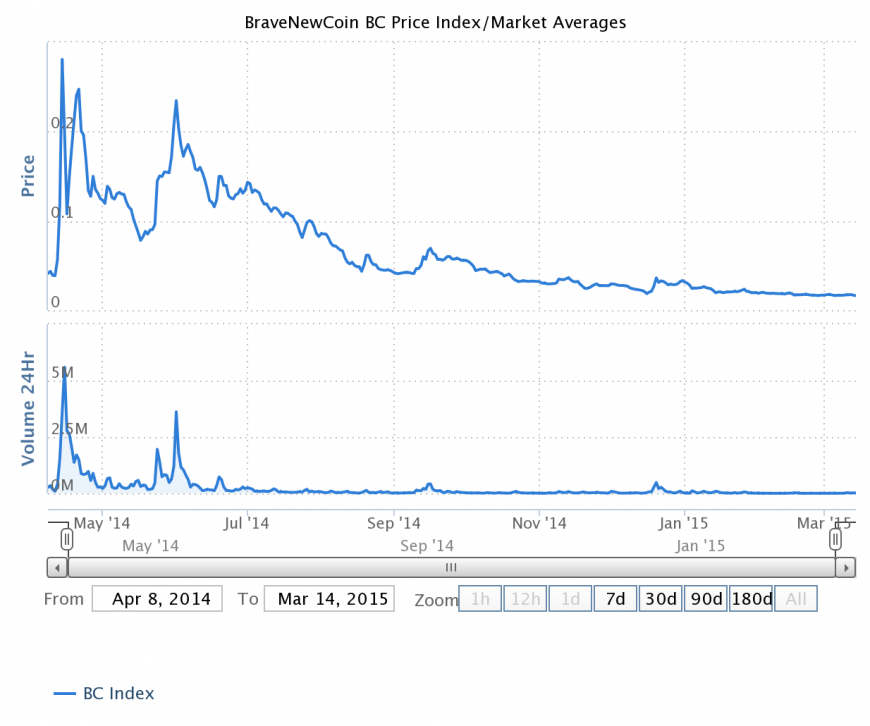

In my previous article empirical research analyzing the data from a number of cryptocurrencies found that value formation occurred at the margin. In other words, it is how many units of a cryptocurrency can be found over some interval with a given amount of mining effort. What’s more is that because only Bitcoin has practical use-value for real world applications, a rational, profit-motivated miner will only mine for an altcoin if they can earn effectively more BTC/day than directing their hashing power at Bitcoin directly. As a result, altcoins find themselves always offered in the Altcoin/BTC marketplace and have the tendency to fall in price over time relative to Bitcoin. In fact, this is what has been observed in the market: over the past six months Litecoin is down 41%; Dogecoin -25%; Peercoin -50%; Reddcoin -50%; Namecoin -43%; Nextcoin -40%; Blackcoin -91%; and so on. The Altcoin200 Index, a BTC-denominated market-cap weighted index of the largest 200 cryptocurrencies excluding Litecoin and Ripple is down over 20% since the start of the year.

If altcoin relative value is ultimately linked to Bitcoin production, the question is what influences the cost of Bitcoin production – that is, mining. The decision to mine for bitcoin comes down to profitability. A rational individual would not undertake mining if they incurred a loss in doing so. There are many miners in competition with one another – whether solo mining operations, home miners plugged in to a pool, or industrial mining farms – who are driven, on average, by the same profit motive. In any competitive commodity market, competition will force the market price down to marginal cost. In modern microeconomics, the theory is that a producer will produce until a level where marginal product = marginal cost = selling price. Therefore, the low-cost producers end up making the most profits, and high-cost producers drop out as they can no longer compete. Such markets exist in the real world to some extent with commodities such as wheat, crude oil, and iron ore. Bitcoin trades on a world market, it doesn’t matter if a Bitcoin is found in China, Europe, or the United States, it will trade at the world market price.

The marginal cost, in the case of Bitcoin, is energy. Because miners cannot (yet) pay for their electricity costs in BTC, the dollar- (or euro or yuan etc.) price of electricity becomes an important variable. The energy efficiency of the mining hardware is also important, as it determines how much electricity will be consumed per unit of mining power. Today, the world average price of electricity is somewhere around 12.5 to 13 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh), and the average efficiency for an ASIC mining rig deployed today is around 0.9 – 1.0 watts per GigaHash/second (or Joules per GigaHash). Knowing these two values, a miner can determine their cost of production per day:

$cost/day = ($price per kWh x 24 hr/day x W per GH/s) x (GH of mining rig / 1000)

It is the average cost across the entire network of miners which regulates the marginal cost for mining. There will be individual mining operations with very low cost of electricity, perhaps in Iceland, or with the latest cutting edge energy-efficient hardware. There will also be miners still running obsolete equipment or in regions with very high electricity cost in hopes that the price of Bitcoin will one day increase sufficiently to cover their daily operating losses. What matters is the average.

The marginal product, or daily production is the number of Bitcoins one can expect to find per day given the power of their mining rig, which is a function of the level of mining difficulty. Using the identity marginal cost = marginal product = selling price, a price of production in $/BTC can be calculated. This objective price of production level serves as a lower bound for the market price, below which a miner would begin operating at marginal loss and presumably remove them self from the network. Because of this theoretical equivalence, and since cost per day is expressed in $/day and production in BTC/day, the $/BTC price level is simply the ratio of (cost/day) / (BTC expected/day).

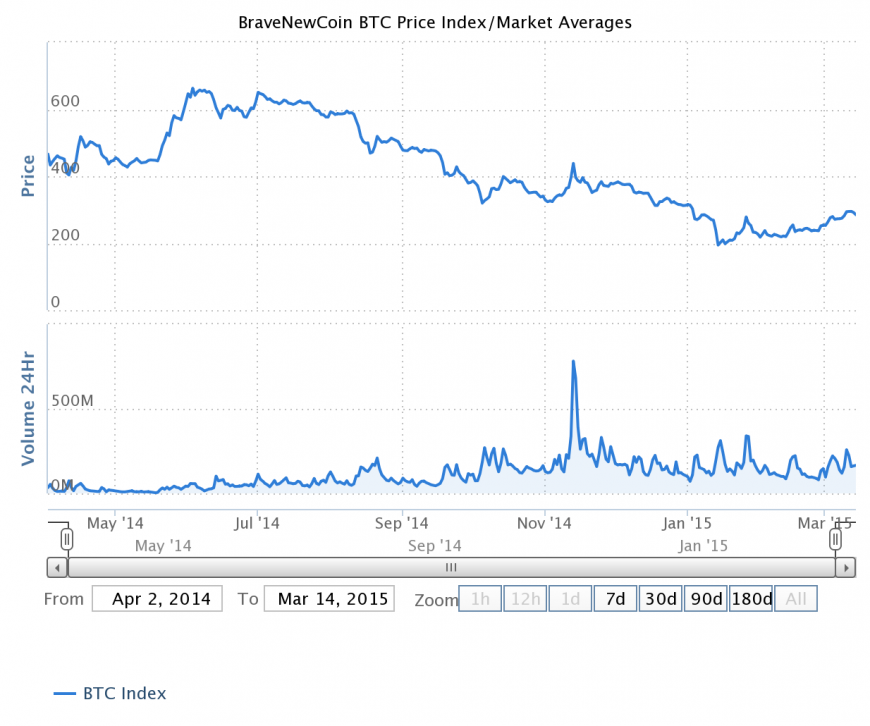

It is useful to consider a hypothetical example. Assume that the average electricity cost in the world is approximately 12.75 cents per kilowatt-hour and the average energy efficiency of an ASIC miner currently deployed is 0.95 J/GH. The average cost per day for a 1,000 GH/s (1 TH/s) mining rig would be (0.1275 x 24 x 0.95) x (1,000 / 1,000) = $2.907/day. The number of BTC that 1,000 GH/s of mining power can find in a day with a difficulty of 47,427,554,951 is 0.010604 BTC/day. Because these two values are theoretically equivalent, to express them in dimensional space of $/BTC we simply take the ratio (2.907 $/day) / (0.010604 BTC/day) = $274.15/BTC. This is surprisingly close to the current market value of around $300/BTC.

This is only an objective calculation, and a reasonable explanation of why the actual market price trades consistently above this value is that there exists a number of subjective motivations for mining that also confer value. There is certainly a speculative premium, and many miners hoard either all or part of their production. The assumption in the objective production model is that all miners bring their product to market for sale each day, which is certainly not the case for everybody. Individual decision makers may undertake mining even at a loss if they believe that there will be a large enough potential upside at some point in the future. Others may be drawn to the anonymity or decentralized nature of Bitcoin.

Another word of caution when considering this cost of production model is that in 2013-2014, there was a large degree of price volatility in the $/BTC price. It now appears certain that this was largely due to deliberate price manipulation and fraudulent automated trading taking place at the Mt. Gox exchange. The Willy Report details trading bot operations whereby customer accounts were pilfered of their dollars in order to artificially drive up the price of Bitcoin, only to collapse and wipe out the money of their customers. This noise, as well as that from other stark price fluctuations following the take down of the Silk Road and other reports of hacking or theft has made back-testing this model using historical price data ineffective.

This cost of production model is useful for an individual miner, or for understanding the value of Bitcoin on a more fundamental level. It informs individual miners of a break-even market price at which to stop mining, and break-even levels in mining difficulty or electricity prices and also be extrapolated.

Mining hardware energy efficiency has already increased massively since the days of GPU mining. A research study found that the average efficiency over the period 2010-2013 was a staggering 500 Watts per GH/s. Today, the best ASIC mining rig available for purchase is somewhere around 0.50 – 0.60 Watts per GH/s. The average energy efficiency right now across the mining network, which is the value which regulates the marginal cost, seems to be around 0.90 – 1.00 Watts per GH/s.

As the average mining efficiency increases, which is a likely result of competition, the break-even price for mining will tend to decrease. This can occur via two primary mechanisms: first, the break-even price will decrease so that miners will continue to operate in competition with each other at lower and lower prices in a linear fashion. For example, if the average efficiency of all miners would be doubled, the break-even price would be halved. The second mechanism is that while this increased competition may induce substantially more mining power to be added to the network, the break-even difficulty level will at the same time increase, accommodating much of that excess mining effort without incentivizing miners to cease.

The difficulty adjustment does act as a stabilizing mechanism, increasing the cost of production as difficulty increases. If a mining rig can find 1 BTC/day on average with today’s difficulty, the same rig can expect to produce less per day if the difficulty increases 10% or 20%. Unlike most commodities where the supply can change quickly to accommodate fluctuations in demand, the supply of bitcoin is hardwired at a steady rate of one block every ten minutes with the difficulty setting adjusting up and down to maintain that linear rate of production through time. If miners are not able to supply enough new coins to meet an influx of new demand, the market price can see increases while the cost of production remains largely the same – inducing more miners to increase their mining efforts. This will cause the difficulty to increase, raising the cost of production until presumably a new break-even level is reached.

One final insight that could have sizable consequences for the objective value of bitcoin relates to the block reward amount and how changes in it will impact BTC/day production. When bitcoin was launched, each block mined was composed of 50 bitcoins. That amount is set to halve every four years, and in 2012 the block reward became 25. The block reward will again halve to 12.5 bitcoins per block, expected mid-September, 2016, and will again in the year 2020 and so on. If we refer to the illustrative example above and substitute a 12.5 BTC block reward for the current 25, the expected BTC/day’ becomes half of 0.010604, which is 0.0005302 per 1,000 GH/s. Given that new BTC/day’, the break-even price for a bitcoin increases to $548.30, holding all else constant (the difficulty and cost per day remains the same). If the market price of bitcoin does not increase in turn, it will suggest that the break-even efficiency will also decrease by half. This could have the effect of eliminating all but the most efficient producers all at once.

Don’t miss out – Find out more today