The mirage of miner centralization

Miner Centralization is hard to define. I present three unsatisfactory definitions, and discover a satisfying fourth (“the cost of the minimal viable mining operation”) along the way. Mostly it is just confusing.

Miner Centralization is hard to define. I present three unsatisfactory definitions, and discover a satisfying fourth (“the cost of the minimal viable mining operation”) along the way. Mostly it is just confusing.

A Quest for Definition

What does “miner centralization” mean, if anything?

Motivation

Certain Bitcoin theorists will complain about a concept called “miner centralization”. Having already tackled a definition of Bitcoin centralization (much to my satisfaction), I was a little confused about the appearance of a new centralization and wanted to explore it.

After searching for weeks, I assembled the following data sources:

- Personal discussions with CoreDevs at Scaling Bitcoin Milan.

- This conversation between Gavin and Adam Back on Trace Mayer’s show.

- This reddit post from Peter Todd about mining pools.

- This video, used by Peter Todd to open his remarks at Bitcoin 2013 Conference.

- This bitcoin-dev email…also from Peter Todd.

- These data on mining pools by Organ of Corti.

- This list of complaints by Rusty Russell.

- This magazine article by Vitalik Buterin.

From what I gathered, the complaints were as follows:

- “…people will only be able to mine if they have large server farms”

- “over time the economically-dependent full nodes are getting more reduced in number because they are moving towards data centers”

- Mining centers will be forced to close, due to ‘rising costs’ and ‘regulations’.

- we should keep money “…out of the hands of the existing corporate system”

- It is bad if the Bitcoin hashrate is managed by a small number of individuals.

- It is bad if miners decline to leave a misbehaving pools.

However, for any complaint to be meaningful, there needs to be an improved alternative. It seems that many of these complain-ers wanted the following:

- Allow anyone to mine, whether they possess a ‘large server farm’ or not.

- Allow anyone to begin mining, without having to purchase expensive items (possibly, of which a ‘large server farm’ is merely one example).

- “…the model is for any one miner to be able to fully participate at the same level as any other miner”.

- “…your resources to keep up …[that cost] only grows at the log of the total transaction volume”.

- Discourage situations where hashrate is managed by a small number of individuals.

- Develop more-effective ways of matching miners with “well behaved” pools.

Ultimately, I boiled this down to two critical concepts:

- The fixed costs of mining. Ie, the (“reuseable”) costs which do not covary with revenue; the minimum expenditure required to set up a new mining operation.

- The minimal quantity of decision-making agents who could control 51% of the network hashrate (or, more generally, some relationship between agency and hashrate-control).

To avoid confusion, I will refer to the first as “mining centralization” and the second as “miner concentration”. The second definition is problematic because there are two classes of agent: firstly, the ‘hasher’ who [1] owns/maintains ASIC hardware, [2] purchases electrical power, and [3] chooses to point the hashrate at some piece of software; and, secondly, the ‘pool operator’ who [1] chooses which block to mine ‘on top of’ (in addition to managing pool membership, setting pool fees, etc) and [2] chooses what to include in the block.

Definitions

This led me, ultimately, to the following definitions:

- Miner Centralization: The fixed costs of mining.

- Managerial Mining Concentration: The quantity of agents one would need to coerce/brainwash, to assume managerial control over 51% of the hashrate.

- Physical Mining Concentration: The total effort required, to seize control of equipment capable of producing 51% of the hashrate.

Checking The Work, With Logic

Those are definitions as recevied from external sources. But perhaps we can do better!

Let’s briefly check the definitions (in reverse).

3. Physical Mining Concentration

Clearly, the last is quite logical – “concentration” is certainly a very real concept, particularly in physics, chemistry, and engineering. When toxins are present in sufficient concentration, organisms will die; when physical substances reach a ‘critical mass’ they can exhibit new phenomena, such as chain reactions.

Moreover, in Bitcoin, users would care about the mining equipment residing all in the same place, for reasons of theft. If one is going to commander a room full of equipement, it is not too much more difficult to commandeer a slightly-larger room – violence has economies of scale. Instead, if spread around the world, adversaries will find the equipment expensive to locate, sieze, and manage.

Finally, the network is programmed to follow the “heaviest” chain – the one with most work. By definition, a 51% hashrate group can be the sole author of this chain.

So our definition –“effort required” to sieze 51% of the hashrate– seems relevant and appropriate.

2. Managerial Concentration

It is an elementary principle of warfare, and game theory (famously in the prisoner’s dillema), that a coordinated group can exhibit different phenomena than an uncoordinated group. So the concept is relevant.

The idea of counting ‘the number of agents’ is an interesting departure from counting ‘dollars’ or ‘effort’. In this way I think the definition makes a unique contribution to the conversation.

1. Miner Centralization

Let’s test the ‘fixed costs’ definition with a thought experiment.

Suppose that a new overwhelmingly effective mining technique “T” is discovered, and further suppose that it is kept secret from everyone. This secrecy would impose a theoretical ‘fixed cost’ upon those who might want to begin mining: the cost of R&Ding technique “T”. In the very short term, this cost would be infinite – whoever controled this information, would in turn control the block creation process.

On the other hand, let us assume that anyone-can-mine, and that they can do so using a magic spell. The magic drains electrical power, but creates valid Bitcoin blocks. This would seem to allow “everyone with cheap power” (reguardless of their location, internet connection, etc) to become a Bitcoin miner instantly.

These results seem consistent with Bitcoiner-concerns, and with a notion of mining centralization.

However, as we will see, it is more consistent with the economic concept of ‘barriers to entry’, than it is to the concept of ‘fixed costs’.

Do These Definitions Make Sense?

Not really. Although I did find a better definition along the way.

Our concepts are:

- Miner Centralization

- Managerial Mining

- Physical Mining Concentration

…and we defined each of them above.

However, I am now going to argue that the first definition is logically incoherent, the second is unmeasureable, and the third is unalterable. As a result, it is probably pointless to talk about any of this.

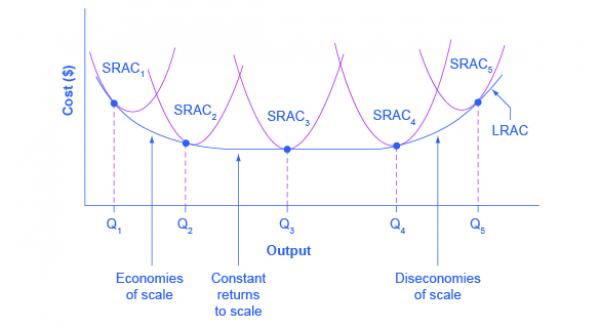

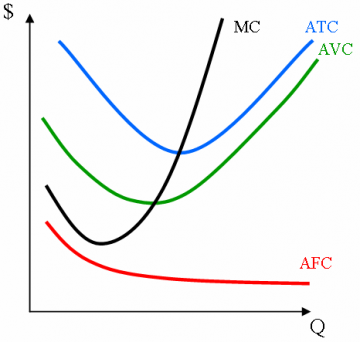

1. Fixed Costs: They’re All Variable

Ultimately, “the cost” is the cost. The distinction between ‘fixed’ and ‘variable’ costs is an accounting convenience (over a subjective time horizon) used to guide the entrepreneur as (s)he performs cost-minimization.

Why Do These Terms Exist?

The field of economics draws a distinction between ‘fixed’ and ‘variable’ costs. The gist of it is that fixed costs can be re-used, but variable costs cannot. For example, a pizzaria might have one oven, which it uses to cook many pizzas per day. For physics reasons, a large oven is ~almost as expensive to heat up as a small oven. But you can fit more pizzas in it (either at once or in rapid succession). The oven is a fixed cost, but the dough is a variable cost (you need 1 dough per pizza). Similarly, the pizzaria may have only one cash register, because (for statistics reasons) patrons are unlikely to all need the register at once.

This distinction is of tremendous importance to a specific producer, in reality, who actually has to optimize a given production-operation tomorrow. This individual will estimate the consumer demand for pizzas, tomorrow, and try to decide how much flour to purchase. If opening a new store, (s)he will wonder what the size oven to buy. A sucessful businessman optimizes these choices, to minimize his total expenditures.

This “cost minimization” is the entire purpose of this distinction. After the costs have actually been minimized, the number(s) are set in stone. It makes no difference, to the owner, if total costs are $15 “average fixed” + $20 “variable”, or if they are 30 “fixed” + 5 “variable”, or $35 “sacred” costs, or 21 “yak” + 10 “veranda” + 4 “azure”. The owner is out 35 bucks, no matter how it’s broken down, or what labels were placed on those accounting categories.

In fact, fixed costs can (and almost always are) amortized over total sales, producing something called “average fixed cost”. So, if a new oven costs $6,000, and lasts for 10 years, and if over those 10 years 30,000 pizzas were sold, then the “average fixed cost” would be, at a minimum, 6k/30k = .20 per pizza. It is the effective oven cost “per pizza”. It was fixed, but it is now “variabl-ized”.

The distinction between fixed and variable costs is merely a tool which assists with the first operation. In reality, all the costs are just “the cost of the investment project” – one single variable cost (or, if you prefer, one single fixed cost).

And I can prove it – notice that fixed costs are defined over an industry-specific time period, beyond which all costs are Variable. Therefore, if we adopted “fixed costs” as a metric for miner decentralitization, mining would always be “more decentralized” in the long run, than it would be over a shorter timeframe. In my opinion this is unhelpful.

Aside: Fixed Costs Aren’t Free

A capital-intensive operation (high fixed costs) usually has an edge: its per-unit costs (“variable costs”) are lower. But it also has a disadvantage: its average fixed costs are higher! A capital-intensive operation must pay for the capital!

In fact, capital is abhorrently expensive, given that every entrepreneur is effectively competing against all other entrepreneurs in the entire world simultaneously. By this, I refer to the opportunity cost of capital – that, instead of building a fancy mining facility, you can take your money and stick it in the stock market, earning 9% nominal per year. Instead of working at the mining facility, you can just go on vacation…and this is even before we discuss risks!

It Really Doesn’t Matter?

By now, angry readers may be protesting that ‘fixed costs’ are, in fact, very important. Industries with high fixed costs tend have few large producers, instead of many small producers. (Implying, of course, that we’d prefer to have many small producers, when it comes to our mining situation.)

After all, shouldn’t we care about what miners find, when they cost-minimize?

I agree that we should. And I look forward to returning to this question later.

For now, I will admit that, at present, miners could minimize their “network costs” (ie stale rates, and orphaned blocks), if all the world’s ASIC chips reported to a single CPU. And certainly, by the properties of statistics, revenue-variance would be lowest if all the world’s miners joined one superpool (as each pool accelerates the law of large numbers, by using a lower difficulty rate and finding more blocks).

The latter, revenue-variance, is not an economy of scale. In fact, by the usual logic of finance, it is “diversifiable risk” and therefore isn’t anything. I look forward to expanding on this in a future post.

However, the former, “network costs”, require some additional explanation.

Is Bandwidth a Fixed or Variable Cost?

Yes

Bandwidth can certainly be “re-used”, in that each miner can send the validated prevBlockHeader to all of his ASIC chips (no matter how many he owns). So I suppose I will admit it is a fixed cost.

On the other hand, I could give an opposite answer! Imagine that full nodes offered a service to miners: for a tiny fee, nodes would tell miners which headers to mine (extraNonce notwithstanding). After all, nodes already know the network state, so they can easily compute the fee-maximizing block, and it’s header. Any node-runner who wished to sell this information, to subscribing miners, could do so. The node would set up a “club” which would charge dues, and the clubs would compete on reputation and brand.

This strongly resembles the behavior of “mining pools” today. And these pools ~all charge fees in percentage terms, which would make “the bandwidth cost” not-reuseable…making it a variable cost.

Crazy, right?

Does this analysis rely on things remaining as they are?

Well, what if pools charged a flat fee, instead of a percentage fee? In a competitive market, this service would be offered at its marginal cost. Since it costs almost nothing for nodes to repeat information they already know, the service would cost almost nothing. (Thus, it would not really be a cost at all, fixed or otherwise.)

Would the market, in fact, be competitive? This depends on the barriers to entry, ie the cost of creating a new full node (which, ironically, is my own definition of Bitcoin Centralization). In fact, it would technically depend on the ‘net’ barriers to entry – by this I mean that many people today run a Bitcoin node today for free, for their own private benefit (therefore, any money they could bring in by ‘upgrading’ to become a pool would be icing on the cake). Thus the barriers to entry are zero.

Therefore, while the marginal cost of providing nodes is zero (in other words, while nodes are being run somewhere by someone), the answer is a strong ‘yes’.

( This result is very amusing to me personally, because it implies that this “new” complaint about mining decentralization is really just the old complaint about “centralization” in disguse. Assuming of course that you agree with me that “centralization” = “the cost of the option to create a new node”. )

Bandwidth Barriers-to-Entry

A better question might be: is there a barrier to entry, such that miners must spend at least X on bandwidth before they can join the mining force? This question is important, because a fixed cost can be a barrier-to-entry (and these entry-barriers are anti-competitive).

Thankfully, the answer is no.

Technically, the answer is “Yes: about ~200 bytes per ~second, downward”. This meager requirement is four orders of magnitude smaller than the ~slowest internet speeds in the world (~256,000 bytes per second). Miners do need to be connected to the internet, but any connection will do.

This is because, while stale/orphan costs did plague the mining network at one time, self-interested, cost-minimizing miners used their entrepreneurial skills to eliminate this cost completely. I refer to three developments: [1] use of pools, [2] use of Corallo’s relay network, and most of all [3] to the use of SPV mining (and its adversary-resistant upgrade: spy mining). These mining techniques allows blocks to be found, many times in a row, without miners downloading any block data. This is accomplished by [1] assuming forgien blocks are valid, if the meet the PoW requirement, and [2] making one’s own blocks empty (or near-empty), which guarantees that the “rushed block” will not accidentally contain a double-spend. This puts all miners on an equal footing, regardless of their internet-speed (at least, while the block reward is the dominant source of revenue).

However, any miners who do invest in greater connectivity, will see greater revenues, as they can more-quickly download-and-verify all preceeding blocks. The sooner this is done, the sooner fee-paying txns can be included in a miner’s block. Thus, an “incentive glitch” in Bitcoin fixed itself: investments in bandwidth yield higher revenues (whereas previously they yielded lower revenues).

Of course, revenues aren’t profits. Higher bandwidth miners have an edge, but they also have to pay for the bandwidth! Thus, the situation is comparable to investments in newer ASIC chips, or a fancier cooling system.

Inconsistent Complaining

If we complain about bandwidth on these grounds, we run a strong risk of inconsistent complaining. After all, BitFury’s miners now ship only in 40 ft marine containers (which is, I believe, the largest shipping container in all of commerce). It ships that way, I am sure, in order to achieve scale economies in both the shipping itself, but also in the cooling of the unit and the installation and operation of the equipment. Those are all easier to reuse “within the BitFury family of products”.

Finding A Definition (!)

Most people who complain about miner decentralization, don’t complain about “minimum investment amounts” (although Peter Todd, to his credit, does complain about both). In the world of theoretical finance, a group of small users would form a corporation, and take advantage of economies of scale. To the extent that they are unable to do this, some users are prevented from mining.

So, finally, we may have stumbled across:

As the cost of ‘the minimum viable mining operation’ increases, miner centralization increases.

This allows miner centralization to increase, if there are ‘kinks’ in the investment-return-function for Bitcoin mining.

Let me explain.

First: if the maximum mining ROI is r%, then eventually all miners must be earning this number. This is because difficulty adjustments will eventually bankrupt any miner who does otherwise. In other words, the question of “Who can mine?” has a naive answer of “anyone”, but a more sophisticated answer of “anyone who can earn r% by mining”. In a sense, there is a natural barrier-to-entry that emerges from the competitive features of mining.

After all, a meritocracy is exclusionary…it excludes people of low merit!

Imagine that, in the year 2015, one needs to spend a minimum of $50,000 “to mine” (see above). If, in 2016, this number has increased to $60,000, we could say that miner centralization has increased. Fewer people are ‘allowed to mine’ in 2016 than were ‘allowed’ in 2015.

However, this definition loses all of its relevance if [a] borrowing is possible, and/or [b] corporations are possible. (With these, small investors are equivalent to large investors.)

It is possible that significant advances in technology (ie, cryptographic identity, reputation, etc) will allow for borrowing / incorporation in an uncensorable way. It is also possible that efforts to restrict ‘Bitcoin Finance’ will fail to gain traction, on grounds of pointlessness.

On the other hand, we may not be so fortunate. If so, we’ll need to keep this metric ready.

In the meantime, let me finish talking about fixed costs.

Intermediaries, and “Variable-ization” of Costs

Provinciality of Costs

The generalization I drew for “network costs” does, in fact, apply to almost every cost.

Consider electrical power. Generating power has returns to scale, of course. Therefore, your power is generated by a few large power plants. So, electrical power generation is a capital intensive, high fixed-cost operation with powerful economies of scale.

However, when you buy power (from the wall-socket in your house), you just pay some price – X $/kWh. This purchase is now a variable cost. The power company (“group 1”) makes power as cheaply as it can, and you (“group 2”) just get charged this minimized price.

The Customer Is Always Right

In our Bitcoin world, pools might sell “bandwidth services” and “transaction servies” to Hashers. A paranoid individual might turn his focus to pools, remark that “there are only ~3” and obsess over pool’s ability to conspire to “censor” transactions.

But where does power truly reside? Miners can switch pools at a moment’s notice. If pools do anything miners dislike, miners can simply leave. And it is easy to create more pools, from the existing full nodes (come to think of it, perhaps it would be helpful if Bitcoin Core shipped with up-to-date pool software, to ensure that barriers-to-entry are always zero).

( The Miner’s reliance on pools is dramatically lower than their reliance on, say, their local power plant. Yet there are no complaints about the plants’ ability to conspire to disable the mining network. Should there be? )

Anyway, it seems to be that pools offer all the efficiency of “minimized network costs”, but with none of the drawbacks.

(Because, you might say, the “evil” fixed costs have been transformed to “safe” variable costs.)

Cost Puzzles in Electrical Technology

What of cheap batteries? Electricity is currently expensive to store, which is why intraday electricity prices vary. But if storage were cheap, the battery could come loaded with cheap eletricity, to power the ASIC over its lifetime. Then a variable cost would become…variable-over-the-time-horizon-of-one-ASIC-lifetime. A battery can’t be “reused” by multiple ASICs, so this cost must be variable.

What if someone invents a solar powered ASIC, that lasts forever? This would seem to set the time horizon to “forever”, at which point the ASIC itself would be one upfront cost…but a non-reuseable one. Since the goal of the ASIC is to produce hashes, and each ASIC would only produce X hashes per time unit, the chip costs (including power-source) would be per-hash, and therefore variable.

However, I am told that today’s miners purchase their power in large 12-month duration contracts. If today’s ASIC chips only have an active lifetime of 12 months, how is the situation today any different from the solar-powered example?

Hopefully, you can see why I find the ‘fixed costs’ argument confusing.

The Other Two

Managerial concentration cannot be measured under adversarial conditions. Physical concentration is unalterable, as it is a function of the geology, civic infrastructure, and physics (which are beyond the reach of computer programmers).

With a large exposition already behind us, these two items should go faster.

2. Managerial Concentration

This section is concerned with questions such as:

- “Who controls the ASICs?”

- “How many of these ASIC-controllers are there?”

- “To what extent are they coordinating with each other?”

I don’t dispute the relevance of this. There are many examples of phenomena changing when there are fewer agents, or when these agents have a greater ability to coordinate.

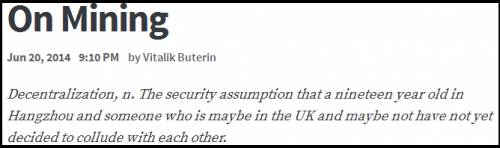

Instead, I oppose this metric on grounds of epistemology. There is no way we can learn how many agents are in control of X% of hashpower.

Fake Dis-Coordination

Coordination is something which can be entirely hidden. Consider two worlds:

- “A”: One where the hashpower is controlled by 1,000 uncoordinated individuals.

- “B”: One where the hashpower is controlled by 1 individual.

The sole individual of world “B” can choose to make his world appear as A. There’s nothing that an unruly mob can do that an obedient army can’t copy – the general can simply command that the soliders pretend to be an unruly mob. The reverse, however, is not the case (the mob cannot effortlessly mimic the discipline of an army unit).

In point of fact, everything we know about Bitcoin miners, and their blocks and their pools, is information that they have volunteered to us.

That’s very charitable of them. However, under adversarial conditions, we can never tell how many agents control the hashpower, be it 2 or 2,000. Worse, these imperceptible executors might, at any time, find it in their interest to deceive onlookers.

This means that any measurements we make, of “miner concentration”, will be at best unfalsifiable, and at worst gravely misleading.

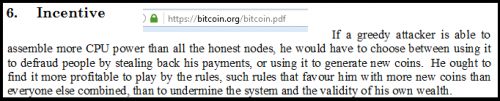

Colluding with Mr. Greed

Instead, I’m most comfortable just assuming that everyone is always in perfect collusion with everyone else. Specifically that all of the hashpower is actually owned-and-operated by one guy, whom we might call “Mr. Greed”. Mr. Greed is looking out for himself, and he wants to make as much money as possible.

I find this assumption realistic, because if the army actually is is more effective (in some way) then the unruly mob, then the unruly mob will tend to resemble an army, anyway.

After all, who really “controls” human choices? We’re all enslaved by our desires.

Why doesn’t Mr. Greed doublespend, you ask? (He can reorganize the chain at any time.) Well, Mr. Greed prefers to keep all of the new coins for himself, rather than undermine the system (and the validity of his own wealth).

This is partially because Mr. Greed can only use his fraud powers to reverse his own payments. And he can only do this for payments which are recent. Payments which have many confirmations, or which belong to channels that were opened a long time ago, are much harder to steal back. (More about this later).

3. Physical Mining Concentration

This concept refers to the ASIC equipment (and the supporting power-supply/cooling), and how easy it is for men-with-guns to storm in and sieze control over all of it.

Problem

It will be easier for an adversary to confiscate the equipment if:

- People know where it is (and you can’t hide it at a moment’s notice).

- It is easy to get to (and you can’t easily move it somewhere else).

And thus it would be bad to have it all permanently installed in one place. The type of adversary who might do this, would probably not even be paying for these men-with-guns himself. Since he would be using “other people’s money”, this is an almost-free way of disrupting the network.

Therefore, this concept is supposedly relevant to Bitcoin.

Response

Firstly, I’m not sure that the risk of confiscation is significantly different from other risks (such as the risk of fire in a mining facility, or risk of equipment failure, employee fraud, etc).

In this sense, the problem is self-correcting: miners earn a higher return, if their ASICs are not confiscated. It is a basic principle of capitalism that we should allow private individuals to manage, control, and “own” the risks associated with their business.

Secondly, but related, we users always have an ace up our sleeve, which is the change of the proof-of-work algorithm from double-SHA256 to something else. This costs us one inconvenience, but it permanently obliterates all existing ASIC equipment. This option provide us with a tremendous defense, one so powerful that it may never need to be used. (However, it also gives miners a reason to care, not only about their own risk of confiscation, but also about that of other miners. The industry can police itself, else it may go extinct.)

The “ASIC equipment”, considered broadly, is never in one place, because by changing the PoW-algo we can reshuffle the deck and force the equipment to reappear all over the world.

Finally, this may indeed be bad, but, if so, there is nothing we can do about it. If ASIC-colocation is cheapest, that is what we will eventually face. The costs of locating the equipment here rather than there, are determined cheifly by factors which are entirely out of our control – the lay of the land, the laws of physics, the power subsidies of a given country. As far as we are concerned, the final destination of the world’s ASICs is as unalterable to us as the height of the average human, or maximum width of a bamboo shoot.

So, if hashpower concentrates in one country, or in one building, “physical mining concentration” could be said to have increased.

But the relevance of the concept is limited to this: we might measure PMC, and not like what we find, and conclude that we should all abandon the Bitcoin project. Tomorrow I will examine PMC in greater detail, but for now I will remark that most of the people who complain about “miner centralization” are specifically not concerned about PMC (at least, sometimes).

In other words, of our three concerns, the only one which is both important and measureable, happens to also be one that we cannot improve or control.

Even more important: not only are we unable to improve PMC, but we can’t make it any worse, either. This measurement is going to be driven entirely by environmental factors, and not at all by factors related to software.

Conclusion

I previously defined “Bitcoin centralization” as “the cost of one’s node-option” (ie, the difficulty of determining that you have, in fact, been paid with funds that are valid). I wanted a precise definition, because I didn’t want to be weighed down with nonsense about “wallet decentralization” and “RIPEMD-160 decentralization” and “Bitcoin logo decentralization” – just because someone can use the word “decentralization” in a sentence, doesn’t mean that we should care about that sentence.

Some felt that my emphasis on nodes was inappropriate, and instead advocated that more attention be paid to miners. I am open to that possiblity, but no one has suggested what, if anything, they think we should pay attention to. No one provided a definition, and when I tracked one down I found a tangled knot of three concepts – when untied, I found a fourth concept. However, each of the concepts seem confusing, and unworthy of conversation.

This is not to say that we shouldn’t talk about mining, or other mining problems. We certainly should. It is merely to say that, in order to have a conversation, the conversation has to actually be about something.

Paul Sztorc is an economist at Bloq, and the creator of Bitcoin Hivemind, Drivechain, and the Truthcoin.info blog. He was previously a statistician in Yale’s economics department.

Don’t miss out – Find out more today